Is another Millenial voice on the internet really what we need?

"Thy ruling thought would I hear of, and not that thou hast escaped from a yoke."

Reading time: 24 Minutes

“Frei nennst du dich? Deinen herrschenden Gedanken will ich hören und nicht, dass du einem Joche entronnen bist.

Bist du ein Solcher, der einem Joche entrinnen durfte? Es gibt Manchen, der seinen letzten Wert wegwarf, als er seine Dienstbarkeit wegwarf.

Frei wovon? Was schiert das Zarathustra! Hell aber soll mir dein Auge künden: frei wozu?

Kannst du dir selber dein Böses und dein Gutes geben und deinen Willen über dich aufhängen wie ein Gesetz? Kannst du dir selber Richter sein und Rächer deines Gesetzes?”

– Friedrich Nietzsche, Vom Wege des Schaffenden in Also Sprach Zarathustra1

In the past weeks I have met many beautiful people and increasingly the topic came up of how I will spend my time after closing the book on my studies.

Thinking about Substack made me wonder whether there is any value in adding another Millenial voice to the conversation or if this is, just like self-improvement, simply masturbation?

To answer this question, I will go into what made the internet great in the first place and what ruined it (I.). When we’ll come to the place where reality and fiction converge (II.), we can finally answer the question: do we really need another Millenial pouring their heart out on the internet (III.)?

I.

An internet shaped by intentional human design

In the early internet, websites were hand-coded and manually curated, either by a staff, an editorial team or a single nerd working with this new technology called computers. Remote islands emerged and were populated by word of mouth only, connections built by bridges of deep blue hyperlinks.

Reminiscing the first time she used the internet in 1993, Amy Hoy writes:

“A well-organized homepage was a sign of personal and professional pride — even if it was nothing but a collection of fun gifs, or instructions on how to make the best potato guns, or homebrew research on gerbil genetics.

Dates didn’t matter all that much. Content lasted longer; there was less of it. Older content remained in view, too, because the dominant metaphor was table of contents rather than diary entry.”

The entire internet in one infinite scroll

This started to change in 2006 when Facebook’s News Feed introduced the habit of looking for content in a single place, albeit a personal one. A user’s feed was curated solely by their personal network and seeing another person’s content required mutual confirmation. Holiday pictures, thoughts on recent events, and shared recommendations were invitations to reach out, making interactions personal and tied to real-life relationships. This was the essential factor in Facebook’s early success.

But it reduced both the diversity and friction that once made the internet exciting, and replaced it with a uniform, infinite scroll more appealing to the average, uninitiated user.

Around the same time, Twitter launched and introduced asymmetrical following, which was quickly adapted by Facebook, opening the personal News Feed to outsiders.

Asymmetrical following meant that now third parties had access to your News Feed. Suddenly friends’ activities mixed with journalists’ political rants, artists announcing tour dates and marketers pushing products. The lines between actual people and personal brands blurred, ultimately leading to today’s content creators needing to be both producers and marketers of their work.

The curated experience became increasingly robotic

As a reaction to the flood of irrelevant updates that came with Facebook’s increasing user base, Facebook introduced algorithmic ranking of content, initially prioritizing:

affinity – the relationship between the user and the content creator,

weight – the level of engagement a post received, such as likes, comments, and shares, and

time decay – how recent the post was

to highlight better content – content more relevant to you, more meaningful.

But these models were quickly abused by marketers, copywriters and SEO strategists. Publishers like Upworthy and Buzzfeed mastered the art of the clickbait, creating pieces that pull readers in with irresistible headlines, only to drag them from paragraph to paragraph, looking for a payoff creating experiences felt misleading at best and deceptive at worst. Unsurprisingly, many people today consume news by reading only the headlines.

In response, Facebook began incorporating new ranking metrics, now prioritizing the time spent on content as a signal of content quality.

So factoring in time spent was a deliberate effort to combat shallow engagement and align the News Feed more closely with user satisfaction.

But doing this, Facebook laid the groundwork to some of the most destructive forces in today’s culture.

The Social Contagion Experiment

In 2012, researchers at Facebook secretly manipulated the emotions of nearly 700,000 users—an entire city’s worth of people—without their informed consent. In collaboration with UC San Francisco and Cornell University, Facebook didn’t just observe behavior, but deliberately altered what people saw, warping their emotions like lab rats in a psychological experiment. The results were as disturbing as they were predictable: emotions are contagious, and Facebook had the power to make people feel happier or sadder without them even realizing it.2

It wasn’t until 2014 that The Atlantic broke the story that made most people I know delete their Facebook accounts:

“We now know that’s exactly what happened two years ago. For one week in January 2012, data scientists skewed what almost 700,000 Facebook users saw when they logged into its service. Some people were shown content with a preponderance of happy and positive words; some were shown content analyzed as sadder than average. And when the week was over, these manipulated users were more likely to post either especially positive or negative words themselves.”3

II.

Gooning in the Stream of Unconsciousness

In Infinite Jest (1996), David Foster Wallace (DFW) tells the story of a film so entertaining and captivating, that everyone who watches it dies.

The viewer falls into a catatonic state, a paralysis of sorts, neglecting basic needs like eating and shitting, eventually starving to death as they remain fixed on the screen until their body gives out.

The state evoked by the film as described by DFW became such an integral part of our reality, that we have an actual word for it: “gooning”.

I’ll let art chad describe it for you:

“The word means to become so transfixed by porn that you enter a hypnotic state for hours and hours as you jerk your penis. [...] What separates gooning from erotic pleasure is the hypnotic state, the transfixation(?) on the subject matter. To enter this state, the subject matter must be as stimulating as possible. [...] The porn viewed in a gooning sesh is usually the most exciting moments. Sometimes three compilations playing side-by-side-by-side in one video. Or images depicting things so extreme, they couldn’t physically exist.”

I think it to be accurate, that gooning is a natural consequence of a certain type of medium. An endless, algorithm-fueled content flow that pushes all the right buttons in your brain physiology to evoke a passive, unreflective, almost dreamlike state that ends only by exhaustion: the viewer falling asleep with the phone in their hand.

TikTok euphemistically calls it For You, Instagram calls it Reels and YouTube calls it Shorts, but I would more aptly call it the Stream of Unconsciousness.

We’re all familiar with short-form media content, and now we have a apt name for it. What is surprising, though, is the extent to which this type of media consumption grips people across all age groups.

Each of these platforms has an estimated user base of 2 billion people. Each. Obviously some are using all three, but most probably it is divided by generational groups with

Gen Z (b. 1997-2012, c. 13-28 in 2025) being short video natives, making TikTok their playground, with heavy Reels use and some YouTube Shorts engagement;

Millennials (b. 1981-1996, c. 29-44 in 2025) grew up with YouTube, so they favor Shorts, while Reels keeps them engaged. Some use TikTok, but less than Gen Z;

Gen X (b. 1965-1980, c. 45-60 in 2025) and Boomers (b. 1946-1964, c. 61-79 in 2025) are comfortable on YouTube, with Shorts as their quick-content fix. Some dabble in Reels, but TikTok is less common.4

No one is spared from the Stream of Unconsciousness.

“How to choose any but a child’s greedy choices if there is no loving-filled father to guide, inform, teach the person how to choose?”

For the people in the book, the actual existence of this film is shrouded in mystery, but the forces of good and evil, manifested as Rémy Marathe, a wheelchair assassin, and Hugh/Helen Steeply, a cross-dressing special agent of united Americas, are eager to find it.

Marathe wants to disseminate the film to every American citizen and make them choose to die from their endless hunger for entertainment. Steeply, well aware that they might lose most of their population, seeks to protect the public from it.

Throughout the book, the two characters discuss their intentions leading up to the following monologue by Marathe:

Almost 30 years later, I start to wonder, whether DFW’s decision of passing prematurely had something to do with the inevitability of his conclusions because it seems like have reached the state of culture that Infinite Jest satirized and warned against.

Have we truly become unable to choose freely, because we are constantly connected to this Stream of Unconsciousness that fully controls our experiences and outlook, not just on the internet, but on life itself?

For the Stream of Unconsciousness our tastes in music, books, films, politics, fashion, and relationships have become nothing but a metric in the algorithm with time spent on a piece being the supreme currency.

With the Stream of Unconsciousness we arrived in a culture where the real and the fake converge in a way that makes it impossible to discern truth and objectivity, which make it impossible to find out, what to use our freedom-for!

And so we rather choose to do nothing, and my our own business, scrolling our lives our away, mutate to fanatics, fry our dopaminergic system and rot our brains rather than to finally stop scrolling.

“It would be one thing if everybody would be absolutely delighted watching TV 24/7. But we have as a culture not only an enormous daily watching rate, but we have a tremendous cultural contempt for TV. Since Newton Minow’s “The Vast Wasteland” has become culture wide, such that now TV that makes fun of TV is itself popular TV. There’s this way in which we who are watching a whole lot are also aware that we’re missing something, that there’s something more.” – David Foster Wallace in a 1996 interview with Charlie Rose5

III.

Thy ruling thought when it comes to using the internet

Seeing all of this, the most obvious reaction would be to throw the phone out the window and never go near the internet again, let alone create more content for it, which some New York based teenagers actually found preferable and founded the Luddite Club, a group dedicated to live social media free lives.

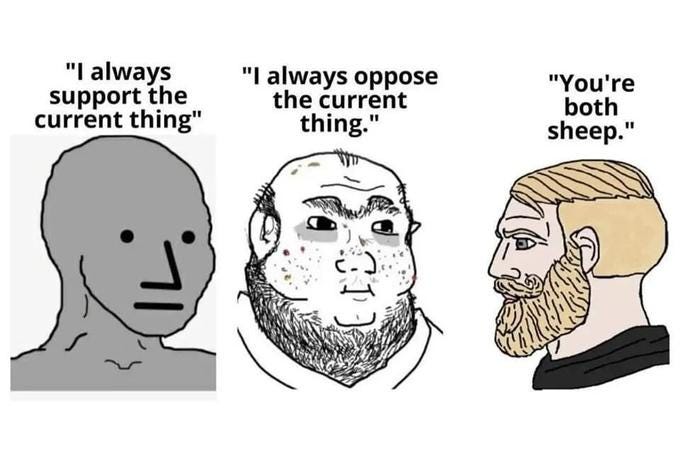

But this is not another article telling you you need to Break Free from the Internet or to reclaim your life by turning to dumbphones. Such articles have become almost an own genre and have little effect as they simply replace one yoke with another.

Rather, this article wants to invite the questions:

What is your ruling thought when it comes to using the internet?

What is the screen time distracting you from? What makes you want to mindlessly scroll

What kind of relationship do you want to have with the world?

As today’s media landscape makes every act of consumption an act of participation, the only choice to make is to whether we participate consciously or unconsciously.

Seeing the internet as a new and very efficient mode of entertainment, unconscious participation is unfortunately the way most people instinctually gravitate towards.

To seek pleasure and to consume, even if it means consuming the most degenerate content for a chunk of our waking hours. This passive way of using the internet invites us to have cheap, flammable opinions, fed by rage bait and hostility towards the unknown, as these remain the last things that make us feel something, after being drained by the degeneracy of grown men of power behaving like children or a grown woman proudly proclaiming to be fucked by 100 guys in one day like it is some kind of achievement.6

The Internet as a Serendipity Machine

To participate consciously requires some work but is infinitely more rewarding: it means to travel back in time and use the internet like the “Serendipity Machine”7 it was originally conceived to be.

Serendipity is what can be called a happy accident, like two coincidences turning a situation to your advantage. While serendipity is partly luck, the chances of it happening can be increased by creating the conditions where unexpected, positive discoveries can happen.

For me, this means to use the internet as a place of connection and expression. A place to my agency, to find a tribe and indulge in my curiosities, putting myself out there and increasing the possibility of luck to happen by consistently working on what is meaningful to me.

But it also means:

Increasing media literacy – Understanding how algorithms work, recognize and mute or block manipulative content from any source.

Shaping the algorithm – Actively curate what I consume instead of letting the algorithm decide for me.

Engaging with content and creators – Not just by liking, commenting, and subscribing, but also by contributing the kind of content I want to see.

Follow people, not platforms – Prioritize real voices over deliberate personal brands and corporate feeds.

I truly believe that these are the tools to shift to a reality that fosters discourse, education, community, agency, and genuine human connection—instead of gooning and brainrot.

Conclusion

Underlying the question of whether we really need another Millenial pouring their heart out on the internet is one basic premise: either one either participates in the discourse by creating or doesn’t participate by not creating.

But this premise is false.

The content we engage with, even passively, is shaping the algorithm, dictating what gets produced, and ultimately defines the reality each of us inhabits.

So, yes, we do need another Millenial speaking out online.

In fact, we need even more people willing to shape the digital spaces we so readily inhabit. We need to consciously focus on creating a human centered internet, where we can be sure that there are actual people interacting with each other, instead of bots and algorithms.

Because if we don’t engage with it consciously, third parties are greedily waiting to decide for us, what is worth believing in.

Further Readings

Everything We Know About Facebook’s Secret Mood-Manipulation Experiment The Atlantic, June 28, 2014.

Sources cited; Research made solely by Grok 3, but it sounds pretty reasonable.

David Foster Wallace: The future of fiction in the information age (1996); also consider, that DFW is talking about TV and not a g-dlike algorithm who knows us better than we know ourselves and anticipates every need and desire before we even have a chance to react.

Louise Perry wrote about this incidence better than I ever could: The myth of female agency (2024).